Overview

Table of Contents

What is a cavernous hemangioma?

A cavernous hemangioma is a collection of abnormal, dilated blood vessels in the brain. A cavernous hemangioma may also be known as a cavernoma, a ‘cav-mal’, a cavernous angioma, or a cerebral cavernous malformation. All these terms are equivalent, meaning they describe the exact same thing.

Other vascular problems can occur in the brain such as aneurysms, arteriovenous malformations, arteriovenous fistula, or capillary telangiectasia. These problems are different from cerebral cavernomas and will be discussed further in other articles.

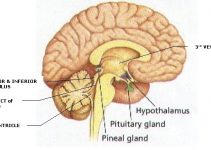

The dilated blood vessels that form a cerebral cavernoma (CCM) can be found in any part of the nervous system (brain and spine) and are organized into a clump that has multiple lobules and has been likened to a mulberry.

This pouch contains multiple blood vessels that are abnormal, meaning they lack some of the key normal parts of a blood vessel such as the muscular layer of the blood vessel and something called ‘tight junctions’ . The muscular layer is usually the middle layer of 3 blood vessel layers and helps provide strength and flexibility to the otherwise brittle blood vessel.

Tight junctions are microscopic attachments that help to make the blood vessel impermeable. Without these key features of a normal blood vessel, a CCM can be prone to leaking blood or ‘rupturing’ and causing a blood clot or ‘hemorrhage’ in the surrounding brain.

What are the causes?

Researchers estimate that CCMs affects approximately 1% of the overall population, making them one of the most common vascular problems that affect the nervous system1.

CCMs are primarily a genetic disease, with approximately 40-60% of patients developing CCM because of a familial genetic syndrome and the remainder of people developing CCMs due to a sporadic genetic mutation2.

The familial form of CCM arises from mutations affecting one of three different genes: KRIT1, malcavernin, and PDC10.

Several different specific mutations within any of these three different genes have been identified, and they all seem to lead to CCM. Researchers believe that these three genes work with other proteins in establishing the integrity of the blood vessels, which is why a mutation in any one of them can lead to the development of a CCM. Researchers have also identified that patients with familial CCM mutations are much more likely to develop multiple CCMs, compared to patients with sporadic CCMs who usually only develop one lesion.

When describing the cause of CCM as sporadic, doctors mean that a patient did not inherit one of the familial genetic mutations known to cause CCMs. Researchers believe that in these patients, CCMs are caused by either random mutations that may develop during cell division or as a result of radiation therapy for another condition.

Are there any symptoms to be aware of?

Patients with CCM may not have any symptoms just from the presence of the CCM. Instead, the most common cause of symptoms in patients with CCM is due to the leaking of blood or hemorrhage into the surrounding brain tissue. Depending on the location of the CCM as well as the severity of the hemorrhage, possible symptoms include:

- New seizures

- Headache

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sudden altered mental status or increased fatigue

- New numbness / weakness/ tingling

- Difficulty with understanding or producing speech

If these symptoms sound like stroke symptoms, that’s because they are. Another way to describe the rupture of a cavernoma is ‘hemorrhagic stroke’ which means that blood leaks into and damages the surrounding brain.

Is there a risk of cavernous hemangioma causing a stroke?

Yes, there is a risk of CCMs causing a stroke. Stroke is the medical word for damage to the brain from changes in blood flow and there are two main types of stroke: ischemic stroke and hemorrhagic stroke. Ischemic stroke is the most common form of stroke and results from a blocked artery which causes a lack of blood flow to an area of the brain.

This is the most common type of stroke and the kind of stroke most people think of when they think of a stroke. A hemorrhagic stroke happens when blood leaks from a blood vessel into the surrounding brain. This is the kind of stroke that can be caused by a CCM.

How is it diagnosed?

While many patients come to clinical attention because of a sudden hemorrhage, not all cavernomas are diagnosed due to symptoms caused by hemorrhage.

A recent research article that reviewed 6 different studies which included over 1600 patients found that 35.6% of patients presented to their doctor with hemorrhage; however, 28.5% of patients presented incidentally, meaning that their CCM was discovered while they were being assessed for another problem3.

If there is a concern for a CCM based on other imaging studies (such as a CT scan of the brain) then usually the doctor will order an MRI of the brain. An MRI offers much better resolution than a CT scan, as well as the ability to obtain different sequences which are very useful in identifying cavernomas.

CCMs have a relatively unique appearance on MRI and because of this are relatively straightforward to identify on MRI.

Any imaging test, such as an MRI or CT scan cannot diagnose something definitively. The only way to know for sure if something is a cavernoma is by looking at a piece of the lesion underneath the microscope.

Usually, this will occur when the neurosurgeon determines the CCM needs to be removed and sends a piece removed during surgery to the pathologist.

Cavernous hemangioma found on the Brain or Spine…what’s next?

If you or a loved one has recently been diagnosed with a CCM, understanding what that means and what may happen next can be very difficult. One of the most important factors is whether the CCM was discovered incidentally or because of certain symptoms. According to recent guidelines, CCMs which are discovered incidentally should be observed, without any immediate intervention such as surgery or radiosurgery.

If a CCM is discovered because it has become symptomatic, then what happens next can depend on several factors.

When considering what to do, neurosurgeons will first determine what caused your symptoms, whether it was a small amount of local hemorrhage or a larger bleed.

Then, they will consider the symptoms caused by the CCM, whether this includes new seizures, neurologic problems like weakness, or other problems such as headache, nausea, or vomiting.

Most importantly, the physician will also factor in the location of your CCM. Some locations, such as the speech centers of the brain, the brain stem, and the spinal cord can be associated with higher risks of surgery than other locations. Based on all this information, your neurosurgeon will determine the safest care for you or your loved one.

What treatments are available?

There are several treatment options available to help manage cavernomas. Some possible treatments for cavernoma include observation, surgery, radiosurgery, or laser ablation. Regardless of the treatment strategy proposed by your neurosurgeon, the key things they will consider are the risk of any proposed intervention versus the risk of harm from the CCM itself.

Observation

Although it may sound counter-intuitive, sometimes the safest ‘treatment’ for a CCM is to carefully follow it with imaging studies over time4,5. In general, people with CCM who are diagnosed because of an incidental finding of CCM are usually managed with routine follow-up MRIs of the brain. The exact timing of the follow up (whether every year or some other interval) has not been established with rigorous research studies, and because of this, there is a wide range of follow-up strategies employed by different neurosurgeons.

In addition to incidentally discovered CCMs, sometimes a neurosurgeon may recommend careful follow-up even after a hemorrhage, if the CCM is in a very sensitive area of the brain or spinal cord. Usually, this is because the risk of attempting surgical removal of the lesion outweighs the risk from a second potential hemorrhage. Some of the most high-risk locations this may be recommended for include brainstem and spinal cord CCMs, as well as CCMs located in the speech centers of the brain.

Surgery

The ‘gold standard’ of CCM treatment is complete neurosurgical removal. Most neurosurgeons will accomplish this using ‘neuronavigation’ to help guide them to the exact location of the CCM, as well as a microscope to help them carefully remove the CCM from the surrounding healthy brain.

The most commonly employed form of neuronavigation around the world allows the neurosurgeon to use a special pointer that shows them where a point they are touching is on an individual patient’s MRI.

This allows them to safely and accurately make a small incision, a small opening in the skull, and find the lesion very accurately within the brain.

Usually, at surgery CCMs look like small, red or purple appearing tangles of small blood vessels. Most often, the surgeon will notice small amounts of blood products, known as hemosiderin, staining the surrounding brain tissue.

Surgical removal may be indicated in several different scenarios. According to guidelines produced by the Angioma Alliance, surgical removal may be considered in the following scenarios4:

- Asymptomatic CCM in an easily accessible location (because of ‘psychological burden’ (i.e.: the patient is extremely distressed by the presence of the CCM), if the patient strongly desires removal to eliminate the need for follow-ups, or because they may need to be placed on anticoagulation).

- CCM with significant hemorrhage in a ‘low risk’ surgical location

- CCM which may be causing medically intractable epilepsy (seizures which are difficult to control with medications and may be caused by the CCM irritating the brain).

The guidelines and overall medical opinion are less clear when it comes to determining when to operate on CCMs which have hemorrhaged and are in ‘high-risk’ surgical locations such as the brainstem or spinal cord.

In general, several sources report that operating on these CCMs may be appropriate after a second hemorrhage, because they may be more likely to hemorrhage than CCMs in other locations.

Ultimately, discussing your or your loved one’s specific case with your neurosurgeon is the safest bet, as many of these decisions depend on an intimate knowledge of a patient’s surgical risk factors as well as the risks of a repeated bleed in the location of their CCM.

Radiosurgery

The use of stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) in the treatment of CCMs is controversial.

SRS is a type of radiation therapy that focuses on many radiation beams, shot from different angles, on a singular point. This type of radiation is used to successfully treat different types of tumors as well as another type of vascular problem known as arteriovenous malformations.

The use of SRS in CCM is less well-established, with some studies reporting benefit, while other researchers contend that SRS does little to alter the natural history of CCM.

Usually, this treatment is reserved for patients with high-risk CCMs in surgically high-risk locations. The Angioma Alliance guidelines state that SRS may be considered in symptomatic lesions in high-risk locations, but that SRS should not be used to treat asymptomatic lesions or surgically accessible lesions.

Laser Ablation

The use of a minimally invasive laser probe to introduce heat energy to kill tumors has been studied in the past. This treatment appears to effectively ablate, or destroy brain tumors.

Because of this, some neurosurgeons have begun attempting to use laser ablation as a potential treatment for CCMs.

Laser ablation may offer a minimally invasive option to destroy CCMs without significantly disrupting the normal, healthy brain surrounding them.

A recent case series of five patients with seizures related to their CCMs reported that four of the five patients experienced seizure freedom after laser ablation and follow up imaging showed that the entire CCM appeared to be obliterated after laser therapy (6).

Laser ablation should still be considered an experimental treatment because long term data confirming the absence of hemorrhage after laser treatment has not yet been reported.

Do Cavernomas always need to be treated?

The short answer to this question is no, every CCM does not always need an intervention to treat it.

The answer to this question for an individual patient is extremely complex and requires consideration of multiple factors, but the bottom line is that the decision of whether or not to intervene ultimately involves weighing the risks of an intervention such as surgery versus the probability of harm without treatment.

In general, while calculating exact risks for a given surgery is difficult, most surgeons can provide a general estimate of a surgical risk considering the CCM location, patient age, and the function of the surrounding healthy brain tissue.

Estimating the risk of not intervening, involves understanding the risk of hemorrhage of a CCM over time. The answer to this question is slightly more complex, as doctors’ understanding of the hemorrhage patterns of CCMs is still evolving.

Currently, analysis of several recent studies suggests that risk factors such as previous hemorrhage or location in the brainstem may significantly increase the risk of CCM hemorrhage3.

What's the prognosis?

The overall prognosis for patients with CCMs is good. Although CCMs may lead to seizures because they irritate the normal brain tissue, the main factor to consider if you or a loved one is dealing with a CCM is the hemorrhage risk.

Previous research studies looking at CCMs have found that this risk appears to be dependent on CCM location as well as previous hemorrhage history. An analysis of previously published studies found that CCMs located in the brainstem have a significantly higher risk of rupture compared to non-brainstem CCMS.

This study found that in patients without a previous history of rupture, the risk of non-brainstem CCM rupture over 5 years was 3.8% compared to an 8% risk of rupture for people with brainstem CCMs3.

CCMs which have not bled before having a lower risk of hemorrhage compared to CCMs which have hemorrhaged before.

A recent study of the natural history of CCMs found that for non-brainstem CCMs, the five-year risk of hemorrhage was 3.8% if they had not bled previously, compared to 18.4% if they had previously bled3.

| Type of CCM | Relative Risk | 5 Year Risk of Rupture3 |

| Non-Brainstem, No Previous Hemorrhage | ↓↓ | 3.8% |

| Non-Brainstem, + Previous Hemorrhage | ↑ | 18.4% |

| Brainstem, No Previous Hemorrhage | ↓ | 8% |

| Brainstem, + Previous Hemorrhage | ↑↑ | 30.8% |

Can a Cavernoma kill you?

Unfortunately, the answer to this question is yes, a CCM can kill you.

While CCMs do not usually cause sudden death, they can cause significant damage to the brain which may lead to disability or death.

This is especially true of CCMs which are in very sensitive areas of the brain such as the brain stem.

The exact risks posed by a CCM are best discussed by a neurosurgeon or neurologist who has reviewed your specific medical history as well as imaging studies and can offer personalized medical advice to you regarding the risks associated with hemorrhage of your CCM.

Is there anything else to be aware of?

The most important thing to be aware of is that the treatment of CCMs is very complex and requires careful consideration by a neurosurgeon.

There are several factors that go into deciding which course of treatment is the best and lowest risk for each individual patient.

Educating yourself, while important, is no substitute for consultation with an experienced neurosurgeon who understands the risks posed by your CCM as well as the risks of surgery.

For more information, we recommend visiting the Angioma Alliance.

References

- 1. Moriarity JL, Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. The natural history of cavernous malformations. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 1999;10(3):411-417.

- 2. Rigamonti D, Hadley MN, Drayer BP, et al. Cerebral Cavernous Malformations. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(6):343-347.

- 3. Horne MA, Flemming KD, Su IC, et al. Clinical course of untreated cerebral cavernous malformations: A meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Neurol. 2016;15(2):166-173.

- 4. Akers A, Al-Shahi Salman R, FRCP Edin M, et al. CCM CARE GUIDELINES 1 Guidelines for the Clinical Management of Cerebral Cavernous Malformations: Consensus Recommendations Based on Systematic Literature Review by the Angioma Alliance Scientific Advisory Board Clinical Experts Panel. 2017.

- 5. Mouchtouris N, Chalouhi N, Chitale A, et al. Management of cerebral cavernous malformations: from diagnosis to treatment. ScientificWorldJournal. 2015;2015:808314.

- 6. McCracken DJ, Willie JT, Fernald BA, et al. Magnetic resonance thermometry-guided stereotactic laser ablation of cavernous malformations in drug-resistant epilepsy: Imaging and clinical results. Oper Neurosurg. 2016;12(4):39-48.