My meningioma story began on Thursday, September 2, 1994, at about 1:30 PM, my ‘lights went out' and I had a meningioma (MD talk for a benign tumor on the brain's covering membrane) removed.

Table of Contents

The Story Of My Battle Against Meningioma

Not only did I survive, but I bounced back in record time thanks to sweat and wisecracks. The tumor doesn't affect the brain per se, but it does press on it, the pressure causing symptoms.

The symptoms resembled Parkinson's disease without the tremor: fatigue, depression, slowness of movement, difficulty in initiating movement, difficulty in falling asleep, muscular weakness.

Early that summer, I'd begun to notice that list of changes in myself.

I'm a workout freak, and the workout habit makes one very aware of the condition of all parts of the entire body. Also, pumping iron three times a week, five hours and more of tennis weekly, skiing on winter weekends — all that elegant sweat — kept me in shape even at 64.

The changes themselves were worrisome.

My tennis game also started to decline, but I put that off to not enough time on the courts.

I played more; I never missed a workout.

Still, my game got worse. Finally, one of my tennis buddies asked, “Are you on any drugs or drops or something?”

“No. I just think I need more work on the courts.”

My gym trainer also began to notice that I was stooping over. She prescribed two added machine exercises that could help correct my worsening posture.

My left foot occasionally dragged as I walked. My speech slurred. My handwriting, always bad, became smaller and worse.

Initiating some simple movement took a long time. I seemed to hesitate — new symptoms all. More to worry about.

These symptoms slowly developed and became more and more apparent. My wife noticed the symptoms, too.

I couldn't put them off any longer. By early August, I'd made an appointment to see my family physician. I suspected Parkinson's disease since my brother has it. The Parkinson's Disease Foundation said familial ties were unlikely, but they sent their brochure and the symptoms seemed to fit.

My family doctor did some quick, external tests and said, “You're certainly showing some symptoms. I think you should see a neurologist.”

On August 17th, the neurologist did more extensive tests: rubber hammer on the kneecap, scraping the cold, metal hammer across my bare feet, walking, turning, nose-touching with eyes closed, etc.

He said, “You show more than just symptoms, let's get an MRI,” (Magnetic Resolution Imaging — a picture of the soft tissue or the brain).

I got the MRI's, one set in black and white and one with a color dye injected. The pictures were taken late in the afternoon of August 18th.

“We'll send these pictures to your doctor by morning, and he'll call you,” the technician said.

By 11:00 AM the next day, my answering machine had a call from my neurologist asking that I call him at his Manhattan office by 4:00 PM. I didn't like the sound of that.

I tracked him down at his Queens office while it was still morning and spoke with him.

“First off, I can see that it's a BENIGN tumor,” he began, “But it IS a tumor and it is affecting you. We KNOW that it IS benign and that's the most important thing.”

I was silent.

“Can you be at my New York office at 4:15 PM?”

“Of course.” I was early.

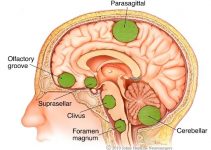

At his office, he showed me the MRI's, the extent of the tumor, and offered his reason for it not being cancerous: the tumor was on the brain's outer wrap…a 99.99% chance it was benign.

“What next?”

“It has to be taken out?”

I had visions of my head wrapped in gauze bandages looking like the mummy in the “Mummy's Curse.”

“Here are the names of two neurosurgeons, both of them excellent men. And, I want you to go on some Parkinson's medication just to be certain.”

All I could think of was how to break the news to my wife. It would hurt her, and I never meant to do that to my lovely women. I love her. I drove home early to wait for her; I began thinking of other concerns: my small business; how it could survive; how long would the recuperation process take; what would I be like when it was over.

After an hour she arrived from school. She must have seen the trouble on my face. I told her as simply as possible, emphasizing the word ‘benign.' We both cried a bit, just hugging each other.

“Don't worry, dear,” she whispered to me. “We'll win. I know it. We WILL win.”

We phoned our children and their spouses.

My wife's strength brought added strength to me.

I knew I was in good shape. I was now very confident. Also, I came to a decision: to be bright, cheery, even impudent and wise-cracking with one and all.

I would use my sense of humor to make all those around me feel as little tension as possible, as little tension for all concerned, including me.

My wife and I used the weekend to begin the process of selecting a neurosurgeon. We selected one of the two recommended surgeons and saw him Monday afternoon, August 23rd.

He was exactly what one should expect in a neurosurgeon: a ‘prima donna assoluto' in a field filled with nothing but prima donnas. He was arrogant, young, supremely confident, filled with nervous energy.

There was also a strange and active sense of humor about the man, found in the highly intelligent or the very talented, and always present in those who have both attributes.

‘Perfect', l thought.

“Oh, I'm not worried about the operation,” he began. “I've done many of them and the tumor will come out easily for me. It's after the operation. Your brain can swell just like any injured part of the body.

We counter that with medication. Hopefully, you'll react well to the medication.

If not, we'll change the medication to a less expensive one which won't give you as much bragging rights with your friends, but it will work nonetheless.”

Another wise-cracker. This was going to be an inspirational, competitive event if nothing else. I knew I could out-wise crack him handily.

“No swelling,” I replied. “My hats are tight enough now.”

We asked, and he mentioned his fee. “And if we don't pay, you put the tumor back, right?” We all laughed.

We bantered about tennis a bit and made a date for a tennis match some months after.

He also set up an appointment with the hospital for September 1st with the operation set for “first thing” in the morning of September 2nd.

Recuperation and length of stay in the hospital were a hit-or-miss affair, entirely up to me. A 10-day stay or two weeks was about average…three weeks in the hospital was also not unheard of.

Little did he know what I had planned: a record recovery and a record “escape” from the hospital. The Guinness Book of World Records awaited.

As he walked out of his office, he concluded, “I've got to warn you, when we play tennis, my serve has been clocked at 90 miles an hour.”

“That's not bad for a SECOND SERVE,” I shot back.

He and his office staff laughed.

And, so the stage was set. I would present a relaxed, tenseless mind in a solid body on a gurney, after which it was the turn of the professionals to do their thing…and on my tumor, too.

The noon-scheduled operation began promptly at 1: 30 PM. By 4:00 PM the day of the operation — some two and one-half hours later — I woke up in the recovery room of the hospital fully cognizant, completely at peace with myself and the world, and saw the beautiful faces of my wife and daughter looking at me.

A nurse said, “Look, he's awake already. Any pain?”

“No. Must I have some?” I replied. My voice evoked smiles and looks of joy on the faces of my family.

“A wise guy,” the nurse responded. “But did you ever see anyone come out of the anesthetic so fast and so completely?” My plan was working.

I'd wisecracked with all, before and after (no ‘during', it is my ‘lights out” period): nurses, aides, the daily blood lab crew (I called them the Count Dracula Blood Bank team), residents, surgeons, neurologist — all on their visits — my wife, my daughter, friends, my ‘roomie'. No one was missed.

The staff enjoyed it; it made the time fly, and soon I was to be on my way home.

So, late Thursday afternoon, on the 2nd of September, the meningioma was out and I wasn't; by Tuesday morning the 7th of the same month, I was out and home. My meningioma stayed at the hospital.

Wednesday, the 8th, I was already pitching a new account by phone from home and taking care of business. The following Wednesday, I saw those principals of that new account at their office and nailed the new deal down.

Was it not ‘fast, fast, fast'? Worthy of Guinness Book entry?

Fast, fast, fast! Sweat and a few laughs helped do the job. No call from Guinness yet.

P.S. The Parkinson's symptoms all disappeared.

AND NOW FOR A NEW BEGINNING.

Pre-Op Before Brain Surgery

You have already decided on your neurosurgeon and his (or her) team. Now is the time to feel quite comfortable with your decision.

You have established a relationship with your surgeon, and know a little about his (or her) personality.

Now is also the time to ask all of the questions that you might have. Write them all down if you have to, so you don't forget anything.

If there is anything that you don't want to know, don't be afraid to tell your doctor!

With the growing adversarial climate of malpractice litigation, most surgeons bend over backward to inform patients of all the potential disasters that might occur during and after surgery.

This can cause patients to be frightened for days, making it impossible for them to function normally. Just be sure to learn all that you really want to, and nothing more.

If, on the other hand, you are the type that reads all of the package inserts and the Physicians Desk Reference every time you take medication, be sure that your surgeon does not pull any punches.

Insist that the surgeon brings it all out…in living color!

Serious Risks

In general, the statistics are quite good, depending upon the type of surgery that you are undergoing. (You can ask your surgeon to rate the degree of difficulty of this particular dive.)

Overall, there is a 2% risk of serious morbidity (real postoperative problems) and mortality with most neurosurgical operations.

Some operations have higher risks because they are known to be exceedingly difficult and dangerous, and occasionally, because they seem too simple.

An example of a difficult operation is that for the large acoustic neuroma. There is a serious risk of loss of facial function on one side of the face and risk of swallowing difficulties after the operation.

The latter could also lead to postoperative pneumonia.

An example of a simple operation with a fairly high postoperative morbidity is the placement of a “shunt” for something called “normal pressure hydrocephalus.”

This patient is at serious risk of developing subdural hematomas or CSF accumulations, requiring further surgery(ies) and even possible removal of the shunt. (All of this can occur because a brain like this has become like a walnut in a shell: smaller than their supportive coverings.)

The bottom line is: ask for all of what you really want to know. But if you are the type who doesn't want to know, don't be afraid to say so!

Pre-Op Necessities

The usual preoperative things that need to be done include bloodwork, heart function evaluation (e.g. EKG), medical clearance by your internist, a chest X-Ray, and possibly a localizing MRI or CT scan to help minimize the surgery. (A kind of “X marks the spot” idea).

If you are undergoing stereotactic surgery, you may require an MRI with localization markers (usually felt-tip pen marks) on your scalp, or the placement of a sort of medieval “frame” that is literally screwed onto your skull, using local anesthetics.

Certain problems may require a cerebral angiogram to be performed so that the surgeon has a “blood vessel” road map prior to surgery. Functional studies (special MRI, EEG, or magnetoencephalography) also may be necessary to guide the surgeon where not to go.

Cerebral blood flow studies (SPECT, Xenon studies or transcranial doppler studies) may be important to show the surgeon the state of your brain's blood supply reserves.

You'll get an IV catheter the night before surgery; you'll be given various medications to prevent seizures, temporarily remove brain water (like medically squeezing a sponge), so the surgeon doesn't need to retract too much during surgery. You'll also be given antibiotics to prevent infection.

If you have an allergy to an antibiotic, make sure everyone knows it.

The night before surgery is usually full of anticipation. More often than not, you'll be the one comforting your family and friends.

If you're afraid, that's only normal. Sometimes sleep is difficult, so don't hesitate to ask for sleeping medication if you want it.

Now is usually a good time to plan for how you will approach the postoperative recovery period.

Many patients tell me that it is very much like gearing up for a sporting event, important business meeting, or even making a New Year's resolution.

You can leave the surgery to the doctors, but you are in charge of your recovery. Think about just how well you are going to be after surgery. A positive attitude is your surgeon's best ally. The two of you are really in this together.

The Brain Surgery Operation

The day has arrived. You have not eaten since last night; you are worried and your family seems either too merry or too somber. You are now “in the system.”

Everyone in the hospital is concerned with your schedule, where to get you to and when.

Things seem to happen too fast until you get to the operating room holding area. The friendliest face that you will see up until this point will probably be the orderly who transports you up to the operating room.

He or she has had much experience as the world's most accomplished, temporary psychiatrist, soothing so many souls on their way to a fearful experience.

More often than not, this kindly face will help carry you through the ordeal, remaining in your memory long after the anesthesiologist fades from view as you fall asleep.

In the holding area both the nurse and anesthesiologist visit with you again, and of course, ask you the same questions.

After that, your surgeon will say hello. Don't be alarmed if he or she asks you “what side your problem is on.” It never hurts to triple check everything.

After a wait (20 minutes or so), you are wheeled into the operating room to a swirl of activity. Nurses (usually three or four), residents (one or two), your anesthesiologist, your neurosurgeon, orderlies and various technologists (possibly), and a whole lot of equipment pack the O.R.

Most patients notice the overhead lights and the blue or green hue that seems to permeate the whole room.

You are moved from the stretcher to the operating table (always too small).

By this time you also notice how cold the room is. Don't be afraid to ask for a heated blanket.

There is a whole warming cabinet next door full of them. If you like music, ask the nurse to turn on the ubiquitous radio or CD player and to play the type of music you are particularly fond of.

By now, the anesthesiologist will have given you some “happy” medicine using the intravenous, and things will begin to both warm-ups and settle down. A certain happy banter fills the room from the chorus of people in the operating room.

You are the star of the show. Soon the anesthesiologist will lean over you and say something like “You are going to sleep now,” or “This should make you feel good.” You will feel a warm feeling and quickly fall off to sleep.

The next thing that you will notice will be the more pleasant lights of the recovery room, wondering. “Has it all begun yet?” But it will already be over.

Post-OP | After Brain Surgery

It's finally over! All of your fears seem to be forgotten. You slowly wake up, look around, and kind of pinch yourself to see if you are still all there.

Just as this happens you may begin to notice the headache that will gradually fade over the next few days. Your surgeon will soon walk in and ask you to say “Hello.”

The relief on his (or her) face might be followed quickly by a phrase like “Well, brain surgery wasn't so bad, was it?” A quick neurologic examination follows and your surgeon shares a quiet moment or two with you.

The next twenty-four hours will be spent in either the recovery room or in an intensive care unit. Usually, a postoperative CAT scan will also be performed during this time, and nurses will stand by you, repeating the neurologic examination every hour or so, while administering the usual post-operative medications.

These usually include pain medications (not too much, because they all want to see you bright and alert), steroids, antibiotics, and anticonvulsants. You will usually be allowed to drink after a few hours, and “advance” your diet with each subsequent meal.

If all is well, you will return to a regular room the following morning. Depending upon the circumstances, a physical therapist will visit you and begin to work with you.

Over the next couple of days, you will increase your activity until you are ready to go home.

During that time you may be seen by various ancillary physicians, such as interns, residents, psychiatrists, radiation oncologists, internists, neurologists, and possibly oncologists.

They will all confer with your neurosurgeon and come up with a game plan prior to your discharge.

Remember, hospitals are quite a lot like the army. The place is full of “hurry up and wait” scenarios.

Physicians and staff all have something slightly different to say. This is sure to create a certain amount of confusion.

Your frightened family and friends are nearby; most of them are too afraid to speak directly to you about anything for fear of saying the “wrong” thing.

The only captain of the ship is your neurosurgeon. You should speak only to him (or her) directly if you have any serious questions or fears. Keep his business card at your bedside at all times.

When in doubt, don't be afraid to call him. Beware of the “all-knowing” intern or family member.

More importantly, understand the stress that your family and friends are under during this time. Beware of the game children play called “telephone;” never accept anything that your doctor has said by way of one, two, three or more intermediaries.

Neurosurgeons tend to be straightforward, kind, and simple in their explanations. We rarely pull punches. We want your trust completely.

If you are convinced that something is wrong and your neurosurgeon tells you that everything is okay, believe him and take a deep breath.

If he tells you that there is a serious problem, believe him and try to concentrate on the logic of the next steps that will get you through the problem.

In medicine, persistence pays; emotional reactions do not. Almost every problem can be resolved, if only the patient and physician remain level headed, logical and persistent, no matter how many steps it takes.

Discharge After Brain Surgery – What Happens Next?

Once you are back home, plan to spend at least the first week concentrating on watching TV, planning further therapy sessions, and maintaining a positive attitude.

After that, you should increase your activity gradually. Listen to your body's signals. If you get tired on Day One, do less on Day Two.

Don't be surprised at how fatigued you might feel, no matter how small your operation.

It is amazing to note how well the body closes down other systems until the challenging part is back on track and in good repair. As a rule, you should give yourself at least six weeks to get “back to yourself.”

Potential problems to be aware of include after surgery discharge:

The incision and bone flap. Most patients complain of itching along the scalp incision, especially up until the time that the sutures (or skin staples) are removed. Keep the wound as dry and clean as you can.

Call your doctor or his assistant if you develop local redness or heat in the area of the incision.

Also, call for any type of fever or rash. Some patients also complain of swelling beneath the skin, followed by swelling around the eye on the side of the operation, and later on the face below the operation.

Remember that any fluid from the brain must travel back towards the heart, passing the eye and face along the way. Some discoloration may also follow the fluid as it travels back to the heart.

Occasionally, the fluid may be normal cerebral spinal fluid escaping into the tissues at the operative site. Do not worry about this; it will go away. Other patients may hear a “clicking” sound at the bone flap site.

This will also eventually resolve as the bone heals. It takes between 6 months and one year for complete healing to occur.

If your surgeon uses a lot of “burr holes” in his flaps, and if he does not routinely fill or cover them, you might complain that you have “bowling ball” sockets in your head. This can be particularly troublesome in patients who are bald.

- Seizures. Most patients must take anticonvulsant medication for six months to a year after their operation. Remember to have your anticonvulsant medication blood levels checked every month or so, especially at the beginning. These medications are usually stopped after a negative EEG for electrical indications of brain seizure activity. Some states do not allow driving during this period, especially if there has been a history of seizures. Ask your doctor to clear you for driving when the time comes.

- Headaches. Headaches almost always disappear within the first weeks after surgery. They should also be easily controlled with analgesics such as Tylenol. If an increasingly severe headache does develop during this time, call your neurosurgeon.

- Physical Therapy. If you have persistent neurological problems such as weakness or speech difficulties, you will more than likely be visited by physical, occupational, or speech pathologist. Make sure that you really concentrate during these sessions, as your benefits will be directly proportional to your efforts.

- Other Medications. Most patients return home with a “tapering” dosage schedule of steroid (anti-inflammatory) medications such as decadron, along with a medication to settle your stomach (e.g. Zantac). These “tapering” schedules may be a bit confusing, so be sure to confirm your schedule with the hospital nursing staff prior to discharge. After returning home, call your pharmacist for help if you need it.

- Discharge to a Rehabilitation Facility. Get ready for the next four to six weeks! Once in a while, you will meet a team of dedicated professionals who will structure a program tailored to your needs. Again, your input is important.